Tagged: archives, material culture, Progressive Era, recorded sound, technology

by J. Martin Vest

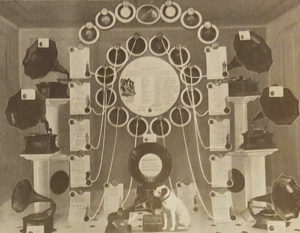

The Graham Talking Machine Company of New York City, 1920. Note the large number of Nipper statues in various sizes. Researcher’s personal collection.

I spent early 2017 at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts while researching the final chapters of my dissertation, “Vox Machinae: Phonographs and the Birth of Sonic Modernity, 1877-1930.” Every morning, I rode the train in from Queens, emerging from the subway tunnels at Lincoln Center across whose broad plaza toddled pigeons and tourists and police. After entering the Performing Arts Library and satisfying the on-duty security guard as to the innocuousness of my satchel’s contents, I generally paused for a word with one of my favorite New Yorkers—a life-size replica of Nipper, dog mascot of the Victor Talking Machine Company. [1]

Or such was my custom until I passed through the Library’s security station one morning and found the statue missing. Earlier that day, I was informed, someone had walked in and grabbed the statue, and but for the quick thinking of Library staff, Nipper would have disappeared amid the anonymous throngs of Midtown Manhattan. For his own safety, Nipper had been relocated to the third floor reading room, taking up residence at the archivist’s station just feet from where I worked.

From the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 22, 1917, pg. 5.

In the weeks that followed, Nipper and I worked together—I poring over phonograph industry periodicals and he at projecting his trademark canine bemusement. I occasionally glanced up from my copies of Phonoscope or Voice of the Victor to meditate on my colleague’s recent brush with disaster. How had the statue come to be in the lobby of the Library? And how had it accrued value (or agency?) such that someone would risk their safety and good name to steal it? This business of Nipper-napping, I determined, was a strange enterprise indeed, and one worth trying to understand.

The many public lives of Victor’s mascot began with the 1887 death of an Englishman named Mark Barraud, among whose belongings included a plucky little terrier named “Nipper” who went to live with the deceased’s brother, the painter Francis Barraud. One day, Francis noticed Nipper listening intently to the sounds issuing from a phonograph’s horn and decided to paint the scene. After several abortive efforts to interest buyers in the image, Barraud sold it in 1899 to the Gramophone Company of London for £100. The painting titled “His Master’s Voice” became the official trademark of the company soon after. Thanks to the marketing efforts of the Gramophone Company’s American affiliate, the Victor Talking Machine Company, Nipper’s image soon spread into nearly every corner of the United States. Victor advertisements appeared in national magazines as well as local newspapers; were projected between films at local nickelodeons; and were even attached to street cars in cities. Nipper featured in nearly all of this advertising [2].

Victor’s dealerships, however, were sites of intense branding, and it was through these brick-and-mortar outlets that so much Nipper-related material poured into the world—and into New York. A December 22, 1917, advertisement in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle provided readers with a list of over 150 Victor dealers in Brooklyn, Manhattan and the Bronx.

A Victor Ready-Made Window display featuring Nipper. Voice of the Victor, March, 1909, pg. 3.

A visitor to any of these dealerships was likely to encounter a universe of Nipper-branded promotional materials—neon signs, “ready-made” window displays , advertising placards, clocks, keychains, floor mats, watch fobs, lapel pins, and more. If period photographs are any indication our imaginary shopper would have found at least one—and possibly dozens—of Nipper statues [Image 6].The first such statues appeared after 1916 when Victor tapped the Old King Cole Papier Mâché Works of Canton, Ohio, to produce them for dealers. RCA-Victor continued to commission Old King Cole and other manufacturers to produce the statues at least into the 1990s.

“His Master’s Voice” doormat produced for the Victor Talking Machine Company by the Pennsylvania Rubber Company of Jeanette, Pennsylvania. Voice of the Victor, April, 1912, pg. 9.

Through the decades and across several corporate mergers, New York’s Victor dealerships continued to serve as conduits for Victor promotional items, so I initially suspected that the Library’s statue had arrived in New York in that torrent of promotional material. As it turns out, however, its origins probably lay elsewhere, and in circumstances revealing much more about Nipper’s cultural power. Pre-World War II “Nipperia” was produced primarily for the dealership, but by the 1950s Victor recognized that Nipper had become a salable good in his own right. Nipper wallets, salt and pepper shakers, tea sets, mugs, tumblers, clocks, nail clippers, electric shavers and even Nipper toilet paper found their way into the American home in the coming years. When in the late 1960s and 1970s RCA-Victor temporarily moved away from the old fashioned dog-and-gramophone trademark the public’s interest in it only grew. Nipper had been an advertisement for phonographs and then a product in his own right. Now he became an object of nostalgic veneration, trafficked in antique shops and yard sales far away from the prying eyes of Victor management—or their accountants.

Nipper statues evidenced the same broad pattern, evolving from agents of the Victor Corporation to semi-autonomous elements in a broader popular culture. Much to the consternation of Victor, the adaptive reuse of Nipper statues sometimes began inside the dealership itself. As early as the 1920s, for example, phonograph dealers began appropriating the statues for their own “off brand” uses, sometimes even positioning Nipper so that he appeared to listen to competitors’ talking machines! Like other articles of Nipperia, however, the statues had evolved by the 1970s into objects of nostalgia among the general public. A 1976 advertisement for Eastern Musical Antiques of West Orange, New Jersey, offered “fully authorized nippers from the original RCA Molds” to the public. These new and fully-licensed Nipper statues generated profit for RCA-Victor. The trade in antique Nipper statues which emerged among collectors, however, did not, nor did the growing trade in unlicensed (and illegal) Nipper “knockoffs” [3].

“His Master’s Voice” watch fob, produced by the Victor Talking Machine Company for use by their dealers. Voice of the Victor, May, 1912, pg. 7.

The provenance of the Library’s statue is murky, but according to curator Jessica Wood, its origins probably date to this moment in the late 70s when Nipper had come to represent a link to the technological and commercial past. Institutional legend holds that it was a promotional item produced by RCA-Victor in 1977 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Edison’s invention of the phonograph. It would have been circulated to institutions and individuals on the company’s distribution list, or to those—like the Library’s first curator of recorded sound, David Hall—with connections to the industry. In all likelihood then, Nipper did not find his way to the Library as part of a wave of unilaterally imposed corporate propaganda dumped into Manhattan through Victor’s dealerships. The statue’s life at the Library and its power to compel rash behavior owes much more to a long and anarchic process of public memory-making—one in which an adoring public had as much say as a Nipper-weary corporate hegemon. Nipper was old-fashioned and he was probably a poor advertisement for cutting-edge consumer electronics. But that is exactly why the public loved him.

Of course, Victor’s own corporate strategies had set the stage for this state of affairs decades prior. Its endless barrage of advertising cleared out a terrier-shaped hole in the American heart, and like a beloved (and probably mythic) childhood pet, Nipper curled right up in it. In that sense, the Victor Talking Machine Company has sent tentacles down through historical time, pulling the would-be thief (and us) into relationships with its creations and structuring our emotional and material worlds. It is probable that Nipper’s assailant was no romantic and merely wanted a sought-after bit of merchandise to unload on the internet. All the same he or she was responding to material, economic and cultural forces loosed more than a century prior. Any of us are free to resist the Victor company’s valorization of its trademark, and we are free to insist that Nipper statues have no intrinsic value. We cannot, however, pretend that our neighbors unanimously agree or that they do not sometimes buy or sell Nipper statues on Ebay for quite high sums. That is a social fact, and one that—for a person in straitened economic circumstances—carries very material consequences.

Victor dealer’s lapel/scarf pin. Voice of the Victor, May, 1912, pg. 7.

As far as I know, Nipper still keeps watch over the third floor reading room at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, doing his best to affect the dignity of his more famous counterparts at the 42nd Street branch. He and the untold legions of other Nippers circulating out there in the wild are still corporate trademarks—properties of an ever-shifting cadre of alphabetically designated global corporations—RCA, GE, JVC, HMV and so on. Who can keep up? Like most dogs, however, Nipper only irregularly, and with mixed results, heeds his master’s voice.

[1] An older image of the Library’s Nipper statue, before he graduated to a life of danger by the security station.

[2] Frederick William Gaisberg, The Music Goes Round (New York: Arno Press, 1977), 25; B.A. Aldridge, The Victor Talking Machine Company (published online by the David Sarnoff Library, http://www.davidsarnoff.org/vtm.html), 17-40; Leonard Petts, and Ruth Edge, The Collectors Guide to “His Master’s Voice” Nipper Souvenirs (London: EMI, 1997), iii-v. The Voice of the Victor, May, 1913, 6. Voice of the Victor, July 1906. The Voice of the Victor, March, 1912. Voice of the Victor, July, 1906.

[3] Leonard Petts and Ruth Edge, The Collectors Guide to “His Master’s Voice” Nipper Souvenirs (London: EMI, 1997).

J. Martin Vest recently defended his dissertation at the University of Michigan. He can be reached at jacquesb@umich.edu.

Receive a year's subscription to our quarterly SHGAPE journal.